When it comes to bullying in schools, we found a big discrepancy between what schools are reporting, and what students are saying.

Channel 2's Sophia Choi learned that more than one-third of Georgia middle and high schools tell the state they haven't disciplined anyone for bullying. At those same schools, more than 16,000 students surveyed said they were bullied at least three times in one month. And more than 8,000 of them said it happens to them many times, or even every day.

For Choi, reporting on bullying is personal. She was bullied when she attended a previously all-white high school in Tennessee. Choi shared her account of what happened here.

Georgia defines bullying as behavior that is deliberate, repeated and involves a power imbalance in which the victim is seen as weak or vulnerable. In state training, "repeatedly" is defined as three or four times.

[READ: Thousands rally behind boy, 5, bullied for wearing nail polish]

Georgia schools report discipline cases to the state every year, and that includes the number of times someone was disciplined for bullying. Last year, schools reported 4,090 discipline cases involving middle and high schoolers.

But in a Georgia Health Survey, when students were asked if they've been bullied three times or more in a month, 64,458 middle and high school students said they had been. The state doesn't ask the question of elementary school students.

Are you curious about your child's school? Here's our lookup tool:

"They're sweeping it under the rug."

Five-year-old Zoey Levandowski knows firsthand about bullying. "He's just doing it to be mean," Zoey said about a student who she says bullies her.

"The boy is three times my daughter's size," father Andy Levandowski said. "The boy's been hitting her every single day. I mean, just all-around everyday bullying."

Levandowski says he's talked to the principal of North Douglas Elementary School, but it hasn't helped.

The Douglas County School System first said it would talk with 2 Investigates about the situation, if Zoey's father signed a privacy waiver. He did. But the school system still refused to do an interview with us about Zoey's complaints. In a statement, the district said it disagreed with the allegations and called them "unsubstantiated."

The district said:

"We have been made aware of the unsubstantiated accusations made by the parents of a North Douglas Elementary School student. The Douglas County School System is fully committed to providing our students with a safe and secure learning environment. Our faculty, staff, and administrators are devoted to keeping our students safe throughout the school day. We wholeheartedly disagree with these allegations and will remain focused on providing for the safety and well-being of every student in our district."

We were unable to reach the parents of the student Zoey says is a bully, because we couldn't obtain his name.

Getting to the root of the problem

For schools involved in anti-bullying campaigns, those numbers can be frustrating.

"I think they're being a little too passive about the situation and they should probably take a more hands-on approach," sixth-grader Starr Haynes told Choi. "Posters aren't really going to do much, so you have to, like, get to the root of the problem."

RECENT INVESTIGATIONS:

- Georgia woman says controversial drug led to series of health problems

- Headaches, help up stairs: What are unnecessary 911 calls costing you?

- APD sergeant accused of multiple sexual assaults remains on force

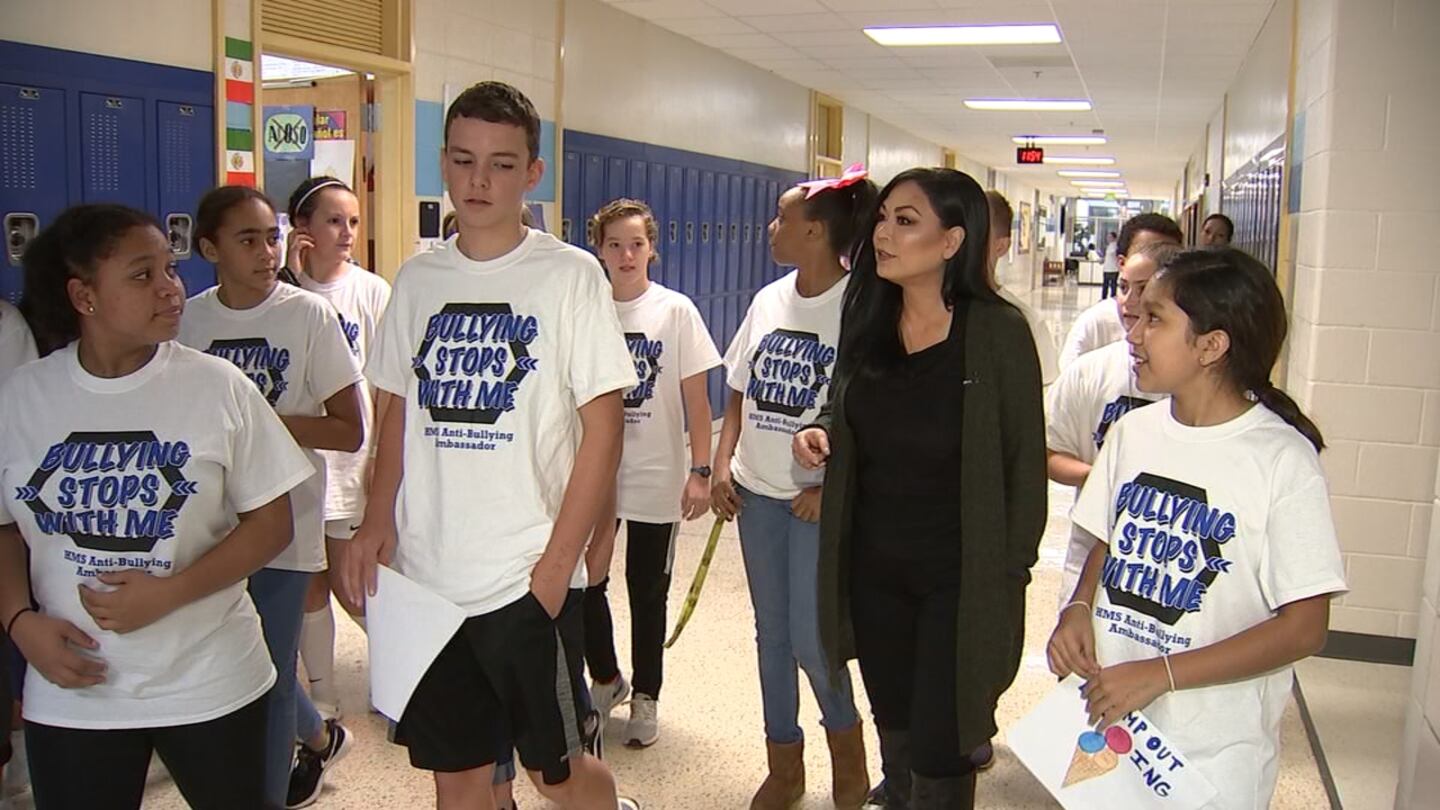

At Henderson Middle School, in DeKalb, some students believe one of the problems is that students are reluctant to tell adults.

That's why the school started a Bully Ambassador program. Seventh-grader Sophia Hook explained the program.

"If you're being bullied, you're going to want to tell your friend about it and so, like, if a student is an

ambassador, then you're looking to feel more comfortable about telling them about the bullying and then they can tell an adult," Hook said.

Others believe school administrators either don't want to or don't know how to deal with bullying.

"This could have been prevented"

Jessica Williams’ son Kerigen Tennyson is a freshman at East Paulding High School. In September, he told her a student was hitting him every day. He said he told a teacher about it but nothing changed.

Williams said Tennyson finally told the boy "If you hit me again, I'm hitting you back." She went to the school, and tried to stop the situation from happening.

"When I went up to the school, I asked for the vice principal and she came in and she sat me down and she wanted to know what I needed," Williams said. "I told her that my son has been getting hit on by another student and they had planned on fighting tomorrow in second period because that's the only class that they have together."

[READ: How to prevent bullying]

"She was like, 'OK, I'll handle it. You don't have to worry about anything. There's not going to be any fighting in this school," Williams said.

But the fight happened. And Tennyson thought he'd solved the problem. But the next day a friend, Tennyson said, a friend of the bully approached him at his locker. Someone shot video while the bigger student sucker-punched Tennyson causing him to be sent to the emergency room.

"Why was this not prevented? It just could have been prevented," Williams said.

The school district wouldn't talk with us about Tennyson's claims, but said it takes bullying seriously. Williams said school officials told her the original incidents weren't bullying because Tennyson participated in hitting.

Still, Tennyson said the boy recently apologized, and said, "You were just fun to pick on."

We were unable to learn the full name of that student, so we couldn't get his side of the story. We tried to reach out to the parents of the friend in the red shirt seen on video who was beating up Tennyson, but were unable to get a comment.

The school district sent us this statement about the claims:

"The Paulding County School District takes reports of bullying very seriously, and schools have a specific protocol that is to be followed whenever an instance of bullying is reported. In this case, the bullying protocol was followed and the report was thoroughly investigated by school administration as well as the Paulding County Sheriff’s Office. The investigation considered evidence that included witness interviews, written statements and videos, and after it was concluded, the matter was then handled appropriately with appropriate consequences for those involved."

Digging deep for answers

When we asked the Georgia Department of Education to point us to a school system that faces bullying head-on, a spokesperson directed us to the DeKalb County School District.

Dr. Vasanne Tinsley, the deputy superintendent of student support and Intervention at DeKalb County Schools, says investigating these cases is never easy.

"It is difficult, but that's why the investigation process is so important," Tinsley said. "It's not a 'What happened? You tell me and it's done.' We are oftentimes digging in deep. We're trying to find out what happened."

Tinsley said that includes a lot of interviews.

"Getting statements not just from the ones involved, but other peers as well," she explained.

[READ: Parents say student wrongfully charged after being attacked by bully]

Those investigations could show that what parents or students call bullying might not be bullying at all.

"When we look at it by definition and we look at it and investigate, it actually comes out to be mutual conflict," Tinsley said. "It actually comes out to be something where a student that was involved in the situation did something at some time before, and this was just a comeback."

Another frustration parents have is that school administrators won't tell them the outcome of a bullying investigation.

"I take the information. I do the investigation. But I can't come back and tell you what happened on that other end because that's violating the privacy of that other child," Tinsley said.

Cox Media Group