Jenna Garland, a former press secretary to ex-Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed, and the first person ever charged criminally with violating Georgia’s public records law, will have her day in court.

Trial is scheduled to start Monday in a case that’s gained national attention from open government advocates, but that carries relatively light punishment for Garland if she’s convicted.

Prosecutors allege Garland committed a misdemeanor by ordering a subordinate in early 2017 to delay production of water billing records requested by Channel 2 Action News for the addresses of Reed and other city elected officials.

On Thursday, Fulton County State Court Judge Jane Morrison denied a defense motion to strike down the criminal statute, allowing the trial to move forward.

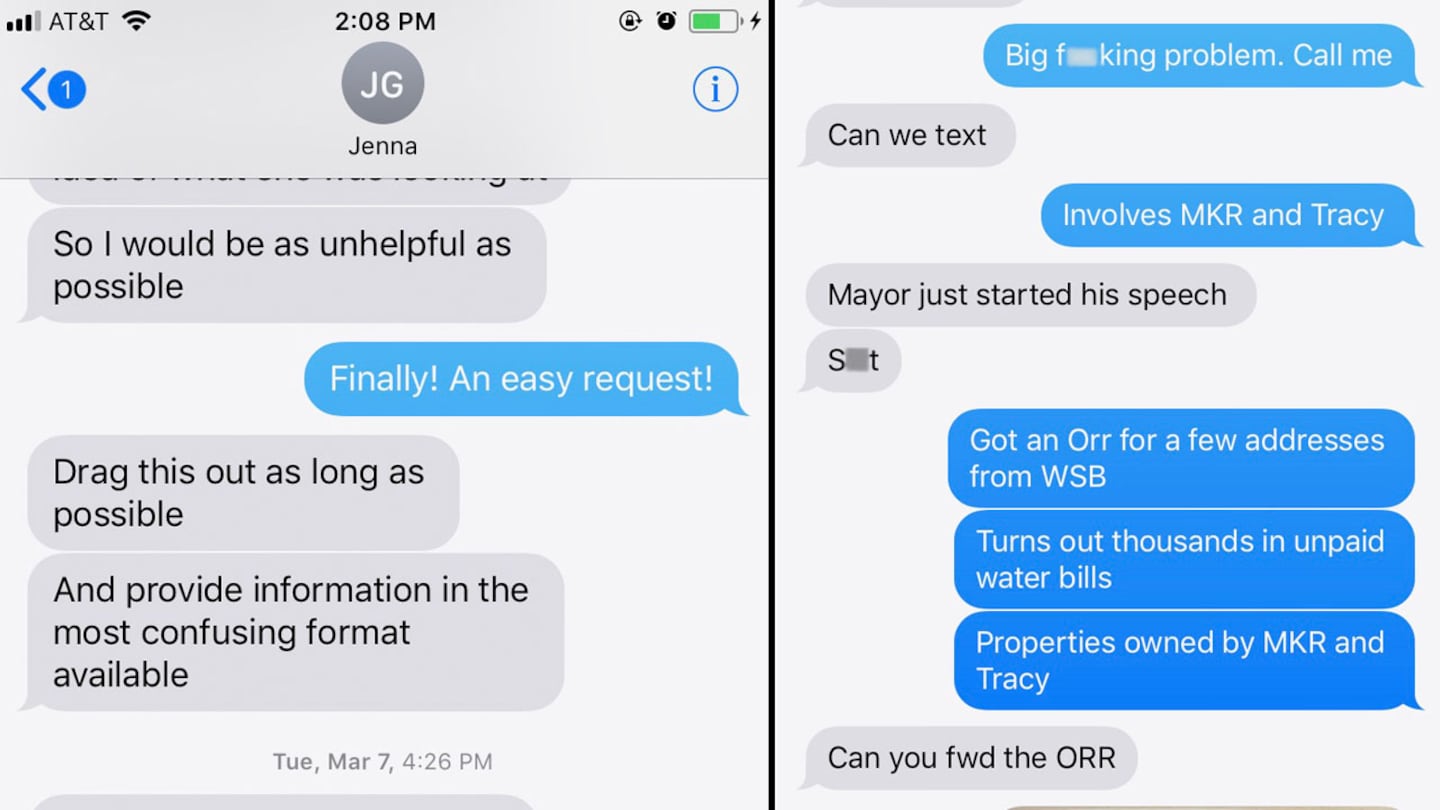

The GBI opened a criminal investigation in March 2018 after The Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Channel 2 published text messages showing Garland instructed the subordinate to “be as unhelpful as possible,” “drag this out as long as possible,” and “provide information in the most confusing format available.”

She later instructed the official to “hold all” records until a Channel 2 producer asked for an update. Those text exchanges form the basis of the two criminal citations.

“The evidence will show that Ms. Garland acted in good faith and that the records requested by WSB-TV were produced within a reasonable amount of time,” said Scott Grubman, Garland’s attorney.

[RELATED: ‘Drag this out': Texts reveal Reed administration’s effort to keep public records from WSB]

Investigations by the AJC and Channel 2 in 2018 revealed a pattern of open records abuses under Reed, including efforts by the city’s communications and law departments to hinder production of public documents. But only Garland’s alleged conduct has resulted in charges.

The Georgia Open Records Act requires public agencies to respond to records requests within three business days and provide records as soon as they are available. But the city dragged its feet on Channel 2’s request for several weeks, and only released records under the threat of legal action.

It’s rare for a public official — in Georgia or elsewhere — to face criminal charges for obstructing the public’s right to know.

Open government statutes across the nation are generally weak, often aren’t well-enforced and have come under assault by lawmakers and special interest groups. Few states have criminal penalties for violating open government laws, and Georgia’s criminal statute — a misdemeanor added in 2012 — is untested.

“If there’s an opportunity to hide from public scrutiny, public officials are going to find ways to do that,” said Dan Bevarly, executive director of the National Freedom of Information Coalition at the University of Florida.

The 2012 statute makes it a crime “to knowingly and willingly frustrat(e) or attempting to frustrate the access to records by intentionally making records difficult to obtain or review.”

Garland, through her attorney, has adamantly denied any wrongdoing. She faces potential fines of up to $3,500 if convicted on both counts, but jail time is unlikely.

Cynthia Counts, a partner at the law firm Duane Morris who specializes in First Amendment cases, said a conviction would show the law has teeth.

“This law is the way we keep our government honest,” she said. “If they can lie and just not give you records, we have no oversight.”

‘Hold all council docs’

Garland and watershed management official Lillian Govus immediately saw the political danger in Channel 2’s February 2017 request for water bills.

“Big (expletive) problem,” Govus said in Feb. 28 a text message, telling Garland it “turns out thousands in unpaid water bills” at properties owned by Reed and his brother, Tracy.

Garland asked if Govus had responded.

“I ain’t stupid,” Govus said.

Mayor Reed’s property had a disconnect notice and his brother’s property was “under investigation for water theft,” Govus texted.

“Jesus Mary and Jospeh (sic),” Garland said.

A week later, Garland told Govus to “drag this out.”

Channel 2 eventually broadened its request to include addresses for all City Council members, but the city repeatedly missed deadlines to provide documents.

Govus told Channel 2 producer Terah Boyd she would release records April 7, but that day Garland instructed Govus to “Hold all council docs until Terah asks for an update.”

It would take a letter from a Channel 2 lawyer for the city to finally release the documents.

Govus, who now lives in Oregon, provided the messages to Channel 2 and the AJC, which published them, triggering the GBI probe. She is expected to testify for the prosecution.

‘An exemplary colleague’

Garland, through her attorney, declined an interview and requested written questions, which she didn’t answer.

Her attorney, Grubman, painted Garland as a victim.

“It is clear that Ms. Garland was unfairly singled out as part of this politically motivated investigation,” Grubman said in a statement.

Reed is a Democrat. Carr, a Republican, brought the criminal charges against Garland after a nearly yearlong investigation. The two men often worked together recruiting businesses to Georgia when Reed was mayor and Carr led economic development for the state.

“Based on the investigation and findings, this office felt this was a clear violation of the Open Records Act,” said Katie Byrd, a spokeswoman for Carr. “For anyone to suggest that it was political is preposterous.”

Reed called Garland “an exemplary colleague.”

“I am proud of Ms. Garland for defending herself and her reputation,” he said in a statement.

At a pre-trial hearing Monday, Garland watched from the gallery with her former boss, Reed’s former communications director Anne Torres. In an email, Torres praised Garland for her “integrity and work ethic.”

“The criminal charges against Ms. Garland are not only frivolous, but unfortunately, attack the reputation of a young woman who deserves to be known for her good character and outstanding accomplishments,” Torres said.

Torres also faced GBI scrutiny after the AJC uncovered texts in which she tried to compel a former Atlanta Beltline CEO in 2017 to delay release of his employment contract.

“We can hold whatever we want for as long as we want,” Torres wrote.

Beltline officials, however, released the records in compliance with the law.

This article was written by J. Scott Trubey, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

© 2019 Cox Media Group